She’s (Pretty) Radical, Smart and Bitchin’

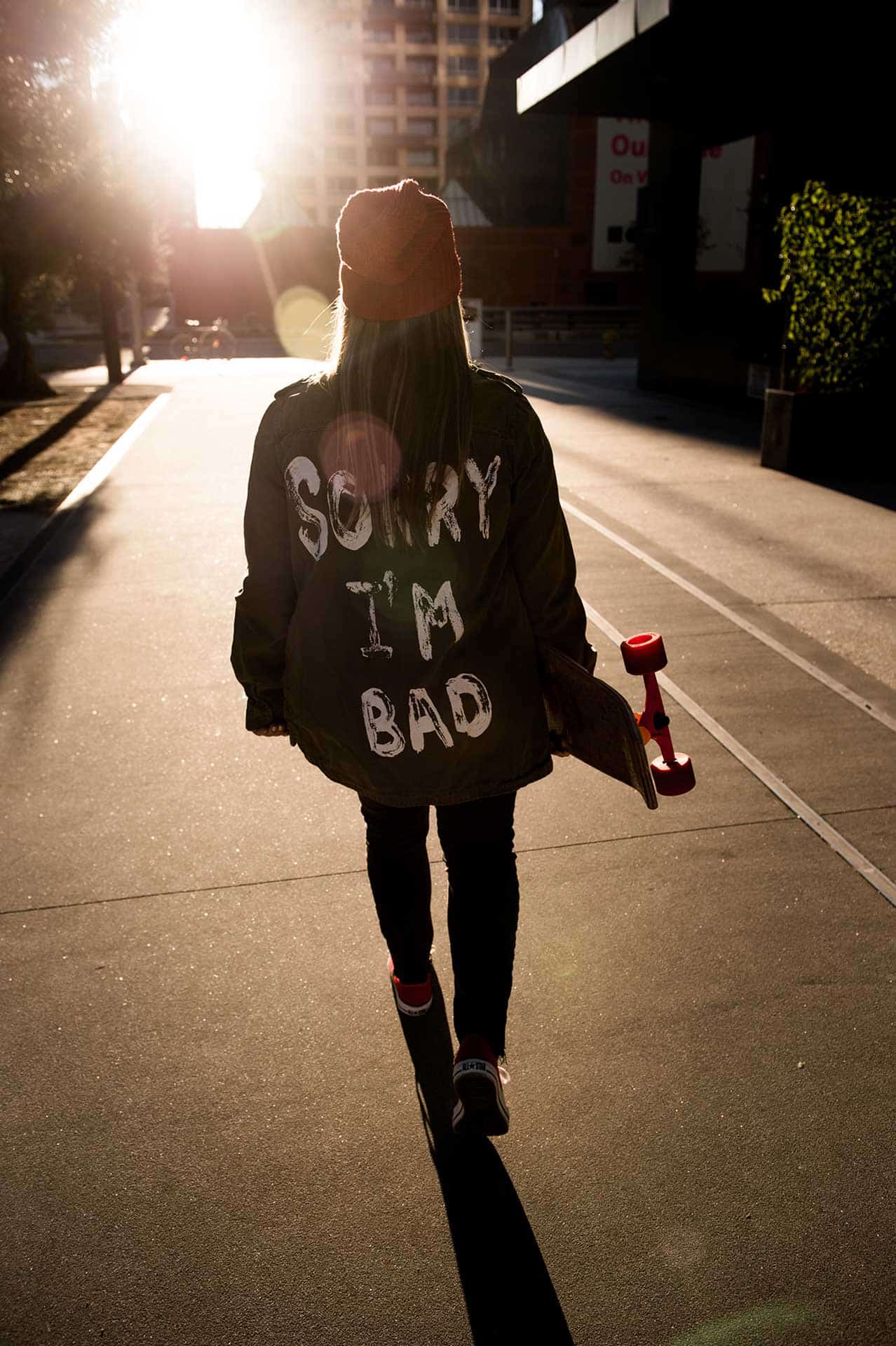

Cindy Whitehead is on a mission to empower the next generation of female skaters to share their stories with the world.

-

CategoryAdrenaline, Experiences, Giving Back, Makers + Entrepreneurs, Outdoor Adventure

-

Written ByMarlene Stang

-

Photographed ByIan Logan

An’ I don’t give a damn ‘bout my reputation

Never said I wanted to improve my station

An’ I’m only doin’ good

When I’m havin’ fun

An’ I don’t have to please no one

An’ I don’t give a damn

‘Bout my bad reputation

Oh no, not me

Oh no, not me

—from the 1981 album Bad Reputation

This anthem by Joan Jett, her musical heroine, is one of Cindy Whitehead’s all-time favorites. And if you talk to Cindy for more than five minutes, you’ll understand why. A spirit of fun, challenging societal norms and living life on her own terms has defined her most of her life.

She is quick to acknowledge, however, that back in the 1970s when she was growing up, most folks living in the South Bay of Los Angeles were very accepting of her as a female skateboarder. “If it wasn’t for the people in the South Bay,” she says, “I probably could not have accomplished all that I have.”

Her grandmother was her first champion and gifted her with a skateboard for her 14th birthday. As the owner of the Tu’u boutique on Pier Avenue and an active community member, her grandmother embodied female empowerment. Her message to Cindy was always: “Mark your own path; do what you want to do. Don’t just follow what everyone else is doing.”

The skateboard that Cindy’s grandmother gifted her had Cadillac urethane wheels, purchased at ET Surfboards in Hermosa Beach. Cindy loved the freedom that skateboarding afforded her. Many of Cindy’s friends and fellow skateboarders were guys, but her best friend was Michelle Kolar—another local girl who would become a national freestyling champion.

Every now and then Cindy and Michelle would encounter other female skateboarders on The Strand or at the local skate parks. “You’d see a few doing freestyle and snake runs,” she remembers. “Vert became popular with the emergence of half pipes and pools.”

The first wave of female skaters from the ‘60s and early ‘70s were falling out of the sport because of injuries or because they were getting older and moving on to other pursuits. Cindy and Michelle were at the vanguard of a new generation.

Also at this time Cindy was attending Mira Costa High School in Manhattan Beach, and she would often ditch her classes to participate in demos. With the support of her family, the school eventually agreed to let her attend half-days in the hopes that this schedule would keep her in school and on track to graduate. She took only core subjects like English and math in the morning and received elective credits to practice skateboarding in the afternoons.

Her skateboarding passion would once again pose a significant conflict of interest, however, when she was invited to participate in her first skate tour. The event required that she travel for three weeks. Compounding the challenge was the fact that, at that time, the school district had instated a new ruling that no student could be absent for more than 10 days per semester before getting kicked out.

The initial solution posed to Cindy and her family was placement in a transitional high school for challenged, on-the-verge-of-dropping-out kids. Both Cindy and her counselor said, “No way,” and her counselor successfully advocated for a tailored curriculum of correspondence courses that she could work into her schedule.

This plan worked really well for Cindy and (eventually) other skaters, who would do their homework on plane rides and whenever they had downtime. Thanks to this game plan, Cindy successfully completed her junior and senior years of high school.

Cindy’s first big skateboarding competition was the freestyle 1978 Hang Ten Skateboard Olympics at Magic Mountain in Valencia. As confident and trailblazing a person as she was (and is), the prospect stressed her out big-time.

She had a vision for how she wanted her routine to unfold, but since her management wasn’t attending to what she saw as very important details, like music, she decided to handle them herself. She also decided that she did not want her friends or family to attend because she believed that their presence at the event would stress her out even more.

Thankfully they defied her wishes and took a ton of pictures that ended up being the only documentation of this seminal moment in her skateboarding career. Skaters from all over the country participated in that competition, and among the women Cindy came in third place.

She participated in many other competitions after the Hang Ten Olympics and became one of the top-ranked professional female vert skateboarders in the U.S. for pool riding and half-pipe. She was also the first professional female skateboarder to be sponsored by Puma and skated professionally until 1982.

Right around this time, skate parks across the country started closing down because parents would sue them whenever their kids got hurt. Cindy decided to “get a job, figure out ‘real life’ and move on.”

After attending UCLA briefly, she found work as a production assistant on several movies and also worked in Mattel’s photo studio. She eventually took a job as a stylist at a magazine called Swimwear Illustrated, which was based in the Bay Area. The magazine was launched by the creator of Runner’s World and served as a great training ground for what would eventually become Cindy’s professional niche.

After working there for only one year, Cindy moved back to the South Bay and landed an agent in Los Angeles who connected her to styling gigs across the area. Cindy began working on print commercials, catalogs and editorial spreads for companies such as Toyota and Volkswagen.

Sports were still Cindy’s passion, however. After a few years her photographer boyfriend (who would eventually become her husband) helped her reexamine her focus. With his support, she came to the realization that she wanted to focus her expertise on sports—even though she was working with some of the biggest companies, actors and musicians in the world.

Her agency dropped her when she told them her decision, and Cindy became a free agent—finding gigs on her own. She coined and trademarked the term “Sports Stylist®” and has worked with some of the top sports photographers in the world for clients like Nike, Adidas and TaylorMade Golf.

But a love for skateboarding never left Cindy, and even though she stopped competing, she never stopped skating. In 2012 she embarked on a renegade adventure that propelled her back into the public eye. Remember “Carmageddon II,” that dreaded final weekend in September 2012 when portions of the 405 Freeway were closed for construction? The royal inconvenience that had most of Los Angeles planning their Netflix queues for the weekend got Cindy and her husband, Ian Logan, strategizing how she could skate down an empty 405 Freeway.

On the morning of Sunday, September 30, police were stationed at every on- and off-ramp of the 405. As they drove around the Sepulveda Pass near Getty Center Drive, Cindy and Ian got pretty discouraged. They were about to turn around and head home when they saw it: a hole in a fence and no police cars in sight.

Cindy recalls that her husband told her to run up onto the freeway and just start skating. She did, and he caught the whole thing on film. They jumped back into their car after only a few minutes because there was a police car stationed at the next exit.

After they got home, they downloaded the images and put one on Instagram. Their use of the hashtag #carmageddon resulted in their post being seen by The Huffington Post, which broke the story shortly after. Soon after, other big media outlets like CBS, ABC, NBC and ESPN were broadcasting the story as well.

Not All Immigrant Stories Are Created Equal

Meet the internationally diverse men and women who created new lives in San Diego.

Get the Latest Stories