Restorer Rod Emory Builds on A Family Legacy of Automobile Excellence

Marauders on the open road.

-

CategoryArtisans, Makers + Entrepreneurs

-

Written byShaun Tolson

-

Photographed byChris Greenwood and Drew Phillips

Call it fate if you want. Destiny, if you believe in that sort of thing. However you choose to look at it, one thing is clear: Rod Emory’s career path is not a surprise. The 45-year-old auto enthusiast was almost born in a hot rod—a modified 1965 short-wheelbase Porsche 911 with RSR flares and a ducktail, to be precise—so it seems only fitting that Emory today has carved out a niche (and a stellar reputation) building discreetly modified vintage Porsches from the 1950s and early 1960s.

Emory’s automotive lineage originated with his grandfather, Nell, who built modified sports cars and hot rods at his Valley Custom Shop in Burbank from 1947 to 1961, later working in the body shop of a Newport Beach Porsche dealership through the 1980s. Nell passed down that car-building passion to his son, Gary (Emory’s father), who grew up harboring his own affinity for Porsche, eventually opening Porsche Parts Obsolete, an automotive shop in Costa Mesa that, as its names suggests, supplied vintage Porsche owners with the original components that they needed to restore their 356s and early 911s to concours-level condition.

Emory cut his teeth in automotive shops at a young age, learning how to sandblast body panels and weld with gas-powered torches when he was 8 years old. By the time he was in high school, Emory was helping his father to customize classic Porsches, but the modified coupes they were building didn’t sit well with Gary’s customers, all of whom were Porsche purists. “You guys are outlaws,” Emory remembers being told. But such criticism didn’t bother the father-son team. “We didn’t care about what other people thought,” Emory says, “so we made these little badges that said 356 Outlaw and put them on the back of the cars we were modifying.”

Decades later, Emory founded his eponymous company, Emory Motorsports, which at first built vintage racecars and provided their requisite track support; however, Emory shifted his company’s focus to the construction of customized vintage Porsche street cars a little more than 10 years ago. For a time, Emory Motorsports was based in Oregon, but its founder returned home to Southern California about a decade ago, setting up shop in a 17,000-square-foot workspace in North Hollywood. That relocation, he says, was critical to the company’s success. “You can’t beat the car culture and everything that surrounds this Porsche community here in Southern California,” Emory declares.

“In the beginning, it was acceptance,” he adds, reflecting on the popularity of his company’s 356 Outlaws, which still wear that homegrown badge. “Then it grew to real appreciation.”

Although Emory’s vehicles all share a recognizable aesthetic, their enhancements are discreet—a trait that Emory is proud of and one that represents a skill that he acquired by watching his grandfather, who Emory describes as a “master of modifying everything but making it look factory built.”

Today, the Emory Motorsports team, which is made up of about 15 technicians, approaches each new project by asking one pivotal question. “When I’m building a car,” he says, “the first question I ask myself is, ‘How would Porsche have done this if they had the parts or if they had modified the model later on?’”

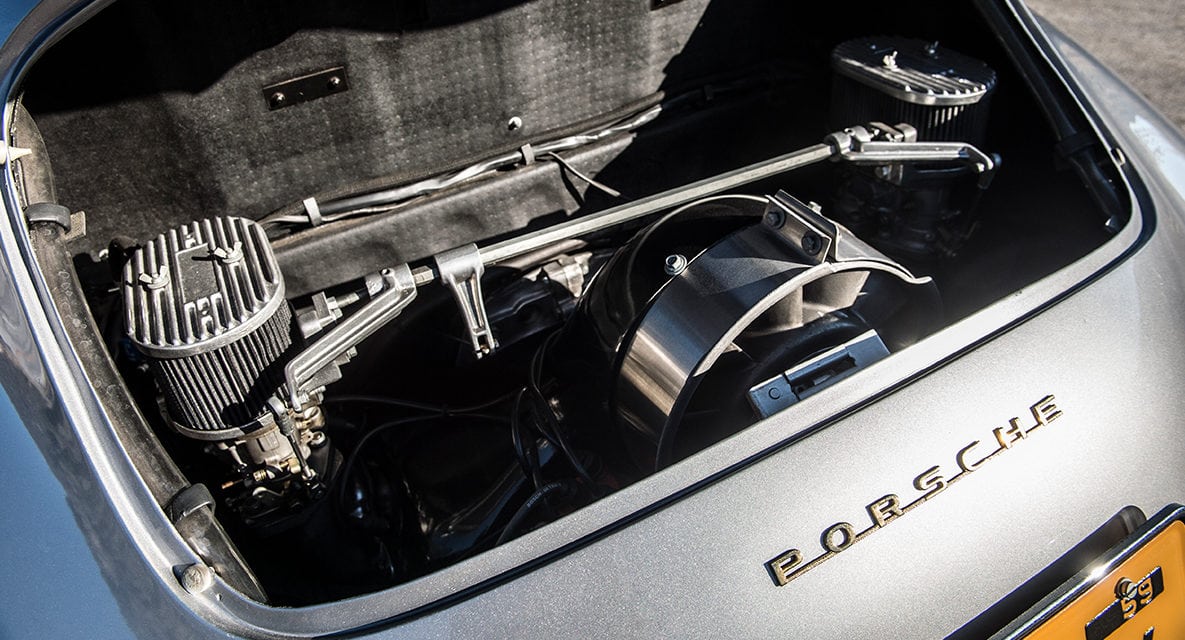

Understandably, that philosophy influences body shapes and styles—earlier this year, for example, Emory judiciously transformed a ’59 Porsche 356 with a compromised roof into a “transitional” speedster—however, the custom car builder also adheres to that same objective when building less visible components. Every Emory Motorsports engine, for example, is bespoke and based on the air-cooled architecture of engines that powered Porsche 911s during the 1990s. “The engine that we’re building is the engine that Porsche wanted to build [at that time] but never did,” Emory acknowledges. “It’s the best of both worlds: it fits in our cars but it’s the best of Porsche’s air-cooled technology.”

On average, Emory Motorsports finishes one car a month; however, each project requires 12 to 18 months of total work. An 18-month-long waiting list also means that prospective owners must wait up to three years to take possession of a new Outlaw. When they do, those auto enthusiasts waste little time racking up the mileage from behind the wheel. In fact, many Emory Motorsports clients immediately take their cars on long road trips. “The average Emory customer is a true Porsche enthusiast who appreciates the history of Porsche and the early vintage designs but loves to drive their cars,” Emory says. “They love the 356, but they just want to be able to drive it every day.”

Because of that, Emory believes that his shop’s location in the greater Los Angeles area is ideal. “When you know roads like Angeles Crest Highway or Mulholland Drive and you get up into the Santa Monica Mountains or the Los Angeles National Forest—or you get out to the desert, like Joshua Tree—there are all these cool places to go driving,” he says. “Within a two-hour driving radius of Los Angeles, you can be at the beach, up in the mountains, in the high desert or low desert or in the snow. To have all of those environments at your disposal it’s just awesome.”

Best of all, a modern-day 356 Outlaw includes all of the necessary features (like air conditioning) to allow those driving enthusiasts to cruise through those environments in total comfort. That includes the peace of mind knowing that their vintage-looking German sports car is also mechanically equipped to conquer any road condition.

“They’re rear-engine, rear-axel drive cars, so they’re pretty darn good in the snow…even off road,” Emory says. “Honest truth, you can pretty much motor these cars anywhere.”

Friday Finds: BBQ Season Kickoff

Fire up the grill…let’s kick off the first holiday weekend of summer with these California standouts.

Monday Moods: “A Little Retro”

Throw it back to your favorite era with these five new earworms.

Get the Latest Stories