In the Hills That Sparked the Gold Rush, Genesee Valley Ranch Is Raising a Special Breed of Cattle

Raising the steaks.

-

CategoryExperiences, Farm + Table, Makers + Entrepreneurs, Sustainability

I’m traipsing through a lush green field, doing my best to keep up with Michele Haskins, the ranch manager at Genesee Valley Ranch in northeastern California. It’s not an easy task, but at this particular moment that has little to do with the terrain.

A patchwork of pastures ranging from 20 to 50 acres in size extends across much of the ranch’s total 1,600-acre footprint. Some of those grazing areas support robust, native grasses that currently stand more than 2 feet high. Trekking through those pastures—I have to assume—would likely be harder, or at the very least slower.

What makes keeping up with Michele so challenging is the simple fact that I want to stop every few paces to gawk at the idyllic landscape that surrounds me. Densely forested hillsides rise above the valley on three of its sides, blending into the angular and rugged, snow-capped summits of Grizzly Peak and Grizzly Ridge—two of the many mountains found within the surrounding Plumas National Forest.

This is a landscape that would have inspired Ansel Adams a century ago, had he seen it. After all, the valley is less than 150 miles away from the northernmost border of Yosemite National Park—a setting that produced many of the iconic images that Adams shot during the first decade of his storied career as a photographer.

“C’mere, c’mere,” Michele says to me, waving me closer. “How close have you ever been to a cow?”

Michele stands only a couple of yards away from one of the 50 or so 2-year-old Wagyu cows that make up this particular herd. “Most people have only ever seen them passing by from the side of the road,” she explains. “To stand in a field and allow them to gather around you and to see them up close and personal, it’s a very unique experience. It really puts into perspective how big these animals are and how strong they are.”

As I take a few steps closer to the herd, a couple of the herd’s members take a few inquisitive steps closer to me. This, I’m told, is not an interaction that occurs on a typical cattle ranch. “It shows you our relationship with the animals,” Michele says, “which is very unique in the production world.”

The entirety of the ranch, from its physical location and valuable natural amenities (more on this later) to its comprehensive operation and direct-to-consumer business model, is unique for cattle ranching. Through its commitment to grass feeding—and with a family ownership that draws on Argentinian roots, years of previous ranching experience and recent success producing estate-grown wines at an innovative winery in Napa Valley—Genesee Valley Ranch is elevating American-raised beef. Best of all, the ranch offers limited access to an exclusive food society that provides a few hundred club members with numerous cuts of 100% Prime Wagyu beef throughout the year.

Property and Pedigree

Genesee Valley Ranch was born more than 150 years ago when Edwin D. Hosselkus, a prospective miner lured from New York to California’s gold country, settled in the valley in 1862. Upon arrival, he quickly built a general store and post office, a granary, a creamery and a blacksmith shop. He named the fledgling town Genesee.

During the Gold Rush, this high-elevation valley was home to a vibrant copper mine, but it didn’t yield much in the way of the rush’s namesake precious metal. Shortly after he arrived in California, Hosselkus pivoted, refocusing his entrepreneurial energies on ranching. He introduced cattle to the valley, and in the process established a multigenerational ranching tradition for his family.

Michele grew up in a family of similar pedigree—she’s the fifth generation of Haskins ranchers. She was initially drawn to the area as a heli-rappeler tasked with protecting the Plumas National Forest from wildfires. But in 2007 she pivoted, just as Hosselkus had done a century and a half before her.

Wanting to start a family, Michele began looking for a safer and steadier line of work and soon answered a newspaper ad seeking help for a local retail beef operation. That brought her to the ranch at Genesee Valley, where her background and knowledge of the trade allowed her to quickly assume the ranch manager’s role.

Adhering to many of the long-standing ranching practices and principles that her grandfather learned from his father—never trust grass that stays green year-round, for example—Michele sought ways to elevate the valley’s beef production in humane and organic ways. Those aspirations received a considerable boost in 2015 when the Palmaz family purchased the ranch.

In 2007 the Palmazes opened the doors to their state-of-the-art winery in Napa Valley, a facility that embraces gravity-flow winemaking and features a wine cave that extends 18 stories into the rocky side of Mount George. It took seven years to build the 91,000-square-foot facility, but along the way—beginning in 2001—the family released vintages of numerous varietals under the Palmaz Vineyards label.

For the first three years, those wines were produced at a facility owned by the label’s consulting winemaker. After that, all facets of production took place at the family’s own winery once the requisite construction was complete.

Shortly after the winery opened, the entire Palmaz family—parents Julio and Amalia, son Christian, daughter Florencia and daughter-in-law Jessica (all of whom live on-site)—discovered that their thriving new enterprise was a true 24-7 operation. Before long they were clamoring for a retreat.

“We wanted a place to escape as a family,” says Florencia, the CEO at Palmaz Vineyards and president of GoodHeart Brand Specialty Foods, “somewhere we could just go and be totally alone and isolated and have some fun and raise our kids the way we grew up.”

Their search for that type of sanctuary brought them into the hills of northeastern California, where they discovered the ranch. It was a fortuitous revelation; however, it didn’t lead to much relaxation.

In her native Argentina, Florencia’s mother worked as a third-generation rancher. Even after immigrating to the United States and later working on a ranch about an hour outside of San Antonio, Texas, she would routinely repeat an adage that her grandfather had often passionately declared: “Only buy a ranch if the animals are chest-high in grass during the middle of the summer.”

Florencia says, “There are only maybe three places in the world where that happens, and we had just found one.”

According to Florencia, buying Genesee Valley Ranch was like scratching an itch. In the family’s case, the itch was a desire to revisit the ranching lifestyle that they had enjoyed decades earlier in Texas. “We were like, ‘Oh my God, we’ve got to do this again! We can’t just use this as a vacation home,’” Florencia says. “We’re just terrible at relaxing. So we were at it again.”

But the Palmazes weren’t just at it again; they were also motivated to revolutionize American grass-fed beef. That required the implementation of some unconventional technology, but—of equal importance—it also meant a dedication to only black Wagyu cattle. America’s Grass-Fed Revolution

Although she moved to the United States with her brother and parents in 1978 when she was only a toddler, Florencia grew up making return trips to Argentina at least once a year. During those trips she constantly listened to visitors and outsiders effusively praise the flavor of her native country’s steaks or slow-cooked barbecue.

“We took it for granted,” she says, “because it’s grass-fed [beef]. Nowhere else in the world can countries commercially feed their populations with grass-fed beef because they don’t grow enough grass. Only in Argentina do you have that luxury.”

Historically, American consumers had to make concessions if they wanted Argentinian beef—provided, of course, that they could gain access to it in the first place. As Florencia explains, the cattle ranching tradition in Argentina centers on Angus cattle—a naturally lean, classic English breed.

To compensate for that leanness and to promote tenderness, the animals are harvested at a younger age than other breeds of cattle, but that produces smaller cuts of meat. And because they’re so lean, those smaller-cut steaks are still slightly tough when compared to the average corn-fed Hereford, Brahman and black Angus ribeyes and tenderloins that take center stage on American steak house menus.

As Michele acknowledges, the emergence of grass- fed Argentinian beef in this country more than 20 years ago was eye-opening for many consumers. “Finally, it was beef with flavor,” she says. “It tastes like what it’s supposed to.”

Nevertheless, that epiphany of flavor was tempered by the aforementioned concessions on size and consistency. When the Palmaz family arrived in the Genesee Valley, they saw what the property offered and immediately recognized its potential. With a plentiful source of natural water provided by seasonal snowmelt high in the surrounding mountains, the pastures produced vibrant grasses that could support as many as 400 cows in an organic way. It was a utopia for grass-fed beef.

If the Palmazes dedicated themselves to raising Wagyu cattle—a larger breed sought after for its rich marbling of fat—they would become the purveyors of a finished product of unparalleled quality: large, immensely tender steaks that are intensely flavorful but also a healthier and more nutritious alternative to what dominated the American beef market. It would be, in no uncertain terms, the ultimate indulgence—the Napa cabernet of beef, as Florencia describes it.

The Palmazes also knew that if they created a direct-to-consumer enterprise—much like how they structured Palmaz Vineyards—they would have wider margins of profitability, which would allow them to reinvest in the operation, improving the health of their herd and integrating greater and more advanced farming practices centered on sustainability. That has set the ranch up for long-term success. It also positions Genesee Valley to be a proponent of change within the grass-fed beef industry.

“We’re seeing an enlightenment of American dining,” says Florencia. “Grass-fed is becoming a better way of life, and there is definitely a huge proliferation of grass-fed beef, thank God! But we have to be very careful that we don’t tip the needle on the grass-fed world and start doing more damage to our lands. There are a lot of grass-fed operations out there that are growing fields—sowing and seeding and mowing—at a rate that’s not sustainable for the land itself. It’s a very real possibility in this country that we get overly focused on grass-fed and do more harm to our fields. Field management should always take priority over grass feeding.”

On that, Genesee Valley Ranch is leading by example.

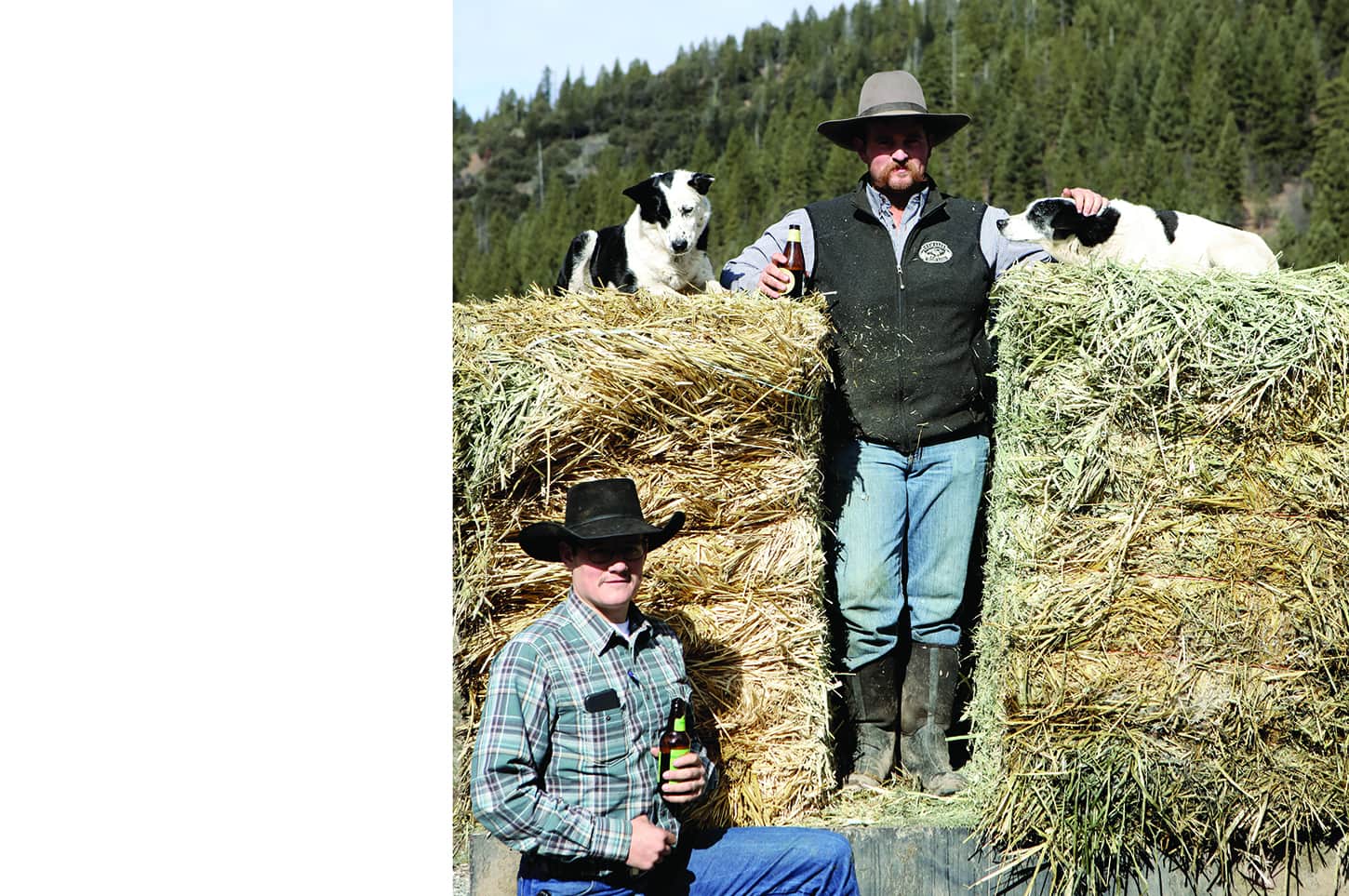

Jesse and Josh, Genesee Valley Ranch cowboys

Elevating a Way of Life

“Perfect.” That’s the word Michele uses to describe the ranch’s setting. It’s a bold statement, one that could easily come across as hyperbole. But the ranch manager defends her position by ticking off a list of the property’s attributes that quickly support her claim.

For starters, 750 acres of the ranch are irrigated by gravity. The flow of snowmelt coming down from the mountains and a network of streams across the valley means that almost 1.2 square miles of pastureland is watered without the use of a single pump. Not only does that help with operational efficiencies, it provides evidence that the ranch’s land is naturally fertile and sustainable. “We have an incredible, healthy soil structure that promotes all the native grasses,” she says.

A large rim of mountains also surrounds the valley, which controls the region’s weather patterns and provides added protection from high winds. Thanks to that defensive ring, the valley’s pastures don’t dry out during the summer, and the valley itself adopts a temperate climate.

And because the valley is set at 3,700 feet above sea level, the ranch experiences four distinct seasons; yet none of them bring harsh or extreme conditions. That seasonal distinction is important, especially as it pertains to the valley’s vegetation. The mantra of Michele’s grandfather—never trust grass that stays green year-round—offers a clue as to why. “The grass needs to go dormant,” Michele says. “It needs to put that energy back into that root system.”

As the ranch manager explains, grasses that must adapt to the seasons—especially slow-growing grasses found at higher elevations—have a higher sugar content than grasses that don’t experience the same seasonal stress. They have a different, more beneficial nutrient profile for grazing animals. It’s what allows Genesee Valley Ranch to raise herds as large as 400 animals on a relatively small footprint of land.

“We need a smaller area and can run a much larger number [of animals] because of the overall nutrient-richness of the fields and the grasses themselves,” Michele says.

The ranch’s small team—two cowboys, two ranch hands and seven dogs—operates an intensive rotational grazing system, where pastures are typically given at least four to six weeks of rest. But the Palmazes and their ranching team don’t rely solely on nature to restore and improve the strength and fertility of their pastures. Leveraging the experiences that owning a winery and caring for vineyards have provided them, the Palmaz family has brought advanced technology to the valley.

In Napa, the family uses a proprietary software program called VIGOR (vineyard infrared growth optical recognition), which through the use of aerial imagery relays vital info about soil moisture and the overall health of the vines. At the ranch, VIGOR produces color-coded maps that chart the effectiveness (and overall impact) of the team’s irrigation efforts.

It also offers them a chance to see which species of grass the cattle are favoring. That allows the team to create a grazing schedule that aligns with the blooming of specific species of grass that the cows seek out during pregnancy or when they’re calving.

“We’re not talking about anything overly complicated or sophisticated,” Florencia says, “but I don’t think there’s a rancher or a farmer in the world who wouldn’t love that luxury [of having aerial photography].”

Genesee Valley Ranch is also fairly unique in its composition. Not only does the ranch operate a cow-calf operation—meaning that all animals in the herd are born there—those animals are also raised on the ranch for the entirety of their lives. Most often, small family-run ranches in the United States will sell their young cattle to larger operations, where the animals will finish their growth and development until they’re ready for slaughter. Not at Genesee Valley.

“These animals never leave the lush, green pasture that they’re born in,” says Michele. “They’re never taken from that, they’re never put into small holding pens, they’re never put in a dry lot or a dusty corral. They’re out there doing exactly what they’re meant to do. They’re grazing, they’re moving freely, they’re as happy as happy can be. From start to finish, they get to experience exactly what an animal is intended to do.”

Michele also utilizes ultrasound technology to evaluate the animals themselves. As she explains, traditional ranching practices rely only on visual cues or basic metrics—an animal’s age or size, for example. Those evaluations don’t offer any assurances that the composition of a cow’s meat has reached its peak. In an effort to bring to market only 100% Prime Wagyu beef, the ranch’s use of ultrasound technology creates greater precision. It’s another parallel that the Palmaz family has drawn between winemaking and ranching.

“In the grape world we get to go out into the field to taste and test the fruit before harvesting,” Florencia says. “But a rancher can’t go cut into the ribeye and say, ‘Oh yeah, that looks good.’ There was no way to field test, and just because it’s an animal and not a plant doesn’t mean that it’s not also subject to the variations of the weather, variations of the nutritional density of the grass or the amount of water we had that year.”

For Michele, the implementation of such technology has elevated her abilities as a ranch manager beyond anything she had previously experienced. “Most of these things that I now get to participate in with the Palmazes are a first for me,” she says. “They have been so gracious in just bringing me along on this amazing ride. It’s been an absolute joy.”

A Taste of the Ranch

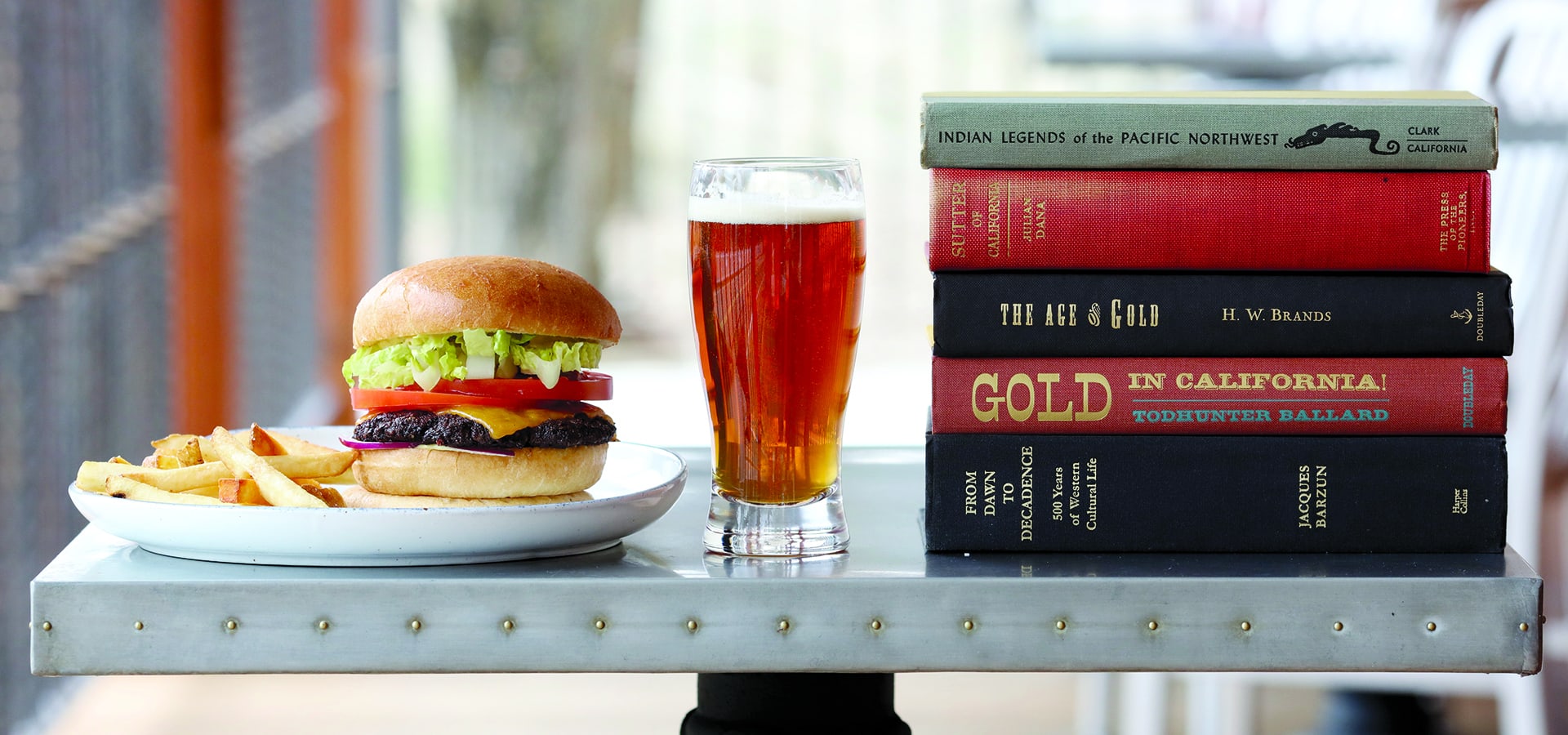

Genesee Valley Ranch isn’t open to the public; however, it is home to a restaurant, the Genesee Store, which occupies the restored, historic building that previously served as the town’s original general store and post office built by Edwin Hosselkus. Set on the main road that runs through the valley and bisects the ranch’s broad network of pastures, the restaurant and its patio offer out-of-towners a good vantage point to catch a glimpse of one of the many Wagyu herds that are often grazing nearby. It also provides locals and visitors with opportunities to understand what organically and sustainably raised, grass-fed Wagyu beef actually tastes like.

Although the restaurant was conceived to be a date-night dining option for the 150 or so residents of the valley, its menu doesn’t always feature luxurious steaks or fancier cuts of beef. In fact, those cuts so infrequently appear on the Genesee Store’s menu that when they do, they’re sold—as Florencia says—“within the milli-second.” New York strips, hanger steaks, tri-tips and tenderloin filets don’t have a regular place within the Genesee Store because those revered cuts (and others like them) are presold through the Brasas Club—a membership program that offers subscribers biannual, quarterly or bimonthly shipments of beef.

As one might expect, beef still leads the menu at the restaurant, only it most often takes the form of traditional comfort food offerings like shepherd’s pie or classically prepared burgers. “The last thing we want to do,” says Florencia, “is alienate a cowboy and not have an honest burger and beer.”

A steak and stout pie is also a best seller. It showcases beer-braised steak tips with carrots and parsnips wrapped in a puff pastry crust. “When it sells out, the chef gets chastised,” Michele remarks.

Those who want to fully experience and enjoy decadent grass-fed Wagyu beef throughout the year can join the Brasas Club, which costs between $525 and $550 per shipment of meat, depending on the desired frequency of deliveries. Members of the club relinquish control over what cuts they receive with each shipment, but Florencia has constructed the program so that cuts are organized by themes and shipments will always include at least one representative from each theme. In that way, members get a chance to experience cuts of meat sourced from each part of the animal.

“I want our customers to explore and understand every possible cut,” she says. “It’s such a tragedy that supermarkets got so lazy in marketing beef. For so many years we forgot what some of the most delicious cuts of beef are just because they weren’t sitting nicely in between kale in the butcher’s case.”

Beyond that whole-animal education, a Brasas Club membership also introduces subscribers to specific cuts that are revered in other countries but are generally unknown here in the United States. These offerings include zabuton (thinly sliced shoulder meat that is beloved in Japan), picanha (the most coveted cut among Brazilian churrascarias) and tira de asado (a chain-like presentation of bone-in short ribs that defines Argentinian barbecue and is best grilled slowly over low heat).

À la carte offerings through the club are also available from time to time. While they’re intended to be supplements for subscribers, nonmembers who are curious to taste the Genesee Valley Ranch difference—but are hesitant to commit to an annual subscription costing at least $1,100—can purchase individual cuts, albeit at premium prices. A duo of 8-ounce tenderloin filets costs $150, for example, while a 2- to 3-pound tomahawk steak will set you back more than $200.

Regardless of how gourmands are introduced to the beef that originates from Genesee Valley Ranch, they’re certain to taste its superiority. As Michele acknowledges, that distinction in flavor and tenderness is a direct result of the ranch’s commitment to treating the animals—and the land upon which they graze—with respect.

“We know them and truly care for them,” she says. “I’m a firm believer that you are what you eat, so why not be something that was well cared for and loved and appreciated? You get that in return in the deliciousness of the end product.”

California Wants You to Hunt … and Help Increase Wildlife Conservation

It may sound counterintuitive, but there’s more to the picture.

10 Unexpected Places You Should See on Foot in Los Angeles

We’re walking in LA.

Get the Latest Stories