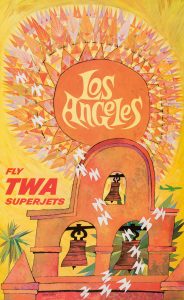

Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985

A new exhibit at LACMA explores the state’s artistic synergy with our southern neighbor.

-

CategoryArts + Culture

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art presents Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985, the first exhibition to explore the full range of design and architecture dialogues between California and Mexico from 1915 to 1985. Found in Translation features more than 250 objects including furniture, metalwork, ceramics, costume, textiles, paintings, sculpture, architectural drawings and photographs, mural studies, posters, ephemera, and film by over 200 artists, architects, designers and craftspeople.

“Found in Translation demonstrates LACMA’s ongoing commitment to Latin American art from the pre-Hispanic period to the present day,” said LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director Michael Govan. “This groundbreaking exhibition highlights the unique strength of an encyclopedic museum. Curators from many different departments leveraged their expertise to contribute to the catalogue and advise on object selection, from works of decorative arts and design, art of the ancient Americas, and Latin American art to costume and textiles, photography, and Modern art.”

“In organizing Found in Translation, we have made it a priority to acquire for LACMA’s collection Mexican and California objects that speak to a dialogue between the two places,” said Wendy Kaplan and Staci Steinberger. “Modern Mexican design treasures include posters from the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, a Hand Chair by Pedro Friedeberg, ceramics by Felix Tissot, and enamels by Miguel Pineda, which are all highlights of the exhibition.”

Political conflict has often marred the relationship between the United States and Mexico, especially during the Mexican-American War (1846–48) and the Mexican Revolution (1910–20). Despite this, the histories of California and Mexico are inextricably linked: both belonged to Spain before 1821 and from that date until 1848, California was part of Mexico. California’s fascination with Mexico emerged in the late 19th century with the pre-Hispanic and Spanish Colonial revivals. The vogue for these styles peaked in the 1920s and 1930s with the added embrace of Mexican folk art and murals. In turn, in the 1930s and ’40s California’s own Spanish Colonial styles became popular in Mexico. And after World War II, Mexico looked to California as a model of modernity—its highways and high-rises promising “The American Way of Life.”

Political conflict has often marred the relationship between the United States and Mexico, especially during the Mexican-American War (1846–48) and the Mexican Revolution (1910–20). Despite this, the histories of California and Mexico are inextricably linked: both belonged to Spain before 1821 and from that date until 1848, California was part of Mexico. California’s fascination with Mexico emerged in the late 19th century with the pre-Hispanic and Spanish Colonial revivals. The vogue for these styles peaked in the 1920s and 1930s with the added embrace of Mexican folk art and murals. In turn, in the 1930s and ’40s California’s own Spanish Colonial styles became popular in Mexico. And after World War II, Mexico looked to California as a model of modernity—its highways and high-rises promising “The American Way of Life.”

The exhibition examines these interdependencies through four themes: Spanish Colonial Inspiration, Pre-Hispanic Revivals, Folk Art and Craft Traditions, and Modernism. All explore how, in California and Mexico, design and architecture are strongly rooted in a sense of place, with local materials and traditions used to form a culture of specificity rather than an “international style.” And each found a more distinct voice through “translations” of the other.

California and Mexico are irrevocably joined by geography, culture, and economics—ties that precede and transcend modern political borders. For centuries, people have moved back and forth between the two places, bringing objects, styles, and images whose meanings were shared as well as altered.

California and Mexico are irrevocably joined by geography, culture, and economics—ties that precede and transcend modern political borders. For centuries, people have moved back and forth between the two places, bringing objects, styles, and images whose meanings were shared as well as altered.

The Spanish Colonial was a dominant style in California and Mexico during the 1920s and 1930s, and its influence lingered for decades. Manifestation on both sides of the border attest to the diverse meanings—about nationalism, place, and social class—attached to what might look like the same visual vocabulary. The revival emerged in California in the late 1800s with romantic depictions of ruins of Franciscan missions from the previous century. Their red-tile roofs, arches, and white stucco walls were appealing, but something grander was required for Golden State exceptionalism.

In 1915, the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego became the first U.S. fair to focus on a regional style. Its elaborate Spanish Baroque architecture had never been used in California, and the revival became a statewide craze. Nostalgia for an imagined past provided a reassuring sense of place for civic and domestic buildings alike. Architects conflated the simplicity of missions with vernacular adobe buildings and elements of the Spanish Baroque.

In Mexico, the Neocolonial (the term for Spanish Colonial revival there) played an essential role in the creation of national identity after the turbulent years of the Mexican Revolution. The new government saw the Neocolonial as a unifying force rooted in the country’s past, combining Spanish and indigenous traditions. In the 1930s, the revival took a domestic turn in the Colonial californiano, when the styles that California had borrowed from Mexico were re-appropriated by that country’s elite for their associations with prosperity and the American good life.

In both Mexico and California, the pre-Hispanic past was integral to the goal of constructing a sense of place. This section explores parallel revivals, as well as Mexico’s influence on California. While Mexico’s elite had celebrated historical indigenous leaders long before the country gained its independence from Spain in 1821, after this period, they particularly invoked Aztec warriors and rulers to symbolize the power of the centralized Mexican state. Starting in the 1920s, the ideology of nation building became more inclusive, encompassing a broader range of Mesoamerican civilizations and social classes. Pre-Hispanic imagery was frequently used to emphasize Mexico’s unique heritage, and representations of the Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec and Aztec civilizations became key emblems of identity.

The art and architecture of Mexico’s ancient civilizations helped establish a visual identity for the New World in both Mexico and California. In Mexico, the emphasis on indigenous cultures also promoted the ideal of mestizaje—melding Amerindian and Spanish cultures—in order to abolish centuries-old class, regional, and racial divisions. When the pre-Hispanic revival was transferred to California in the 1920s, it lost much of its nationalistic fervor. In the 1930s and 1940s, it sometimes served a political agenda of hemispheric harmony, spread by the U.S. government and by Mexican artists, such as Diego Rivera. Until reappropriated by the Chicano civil rights movement in the late 1960s, however, the pre-Hispanic revival styles in California were often no more than an exotic veneer applied to theaters and hotels.

Artists and designers in both Mexico and California romanticized the former’s indigenous artisans, adopting elements of traditional crafts and reimagining native rituals. In Mexico, the post-Revolution government elevated the handcrafts (called “popular art”) and customs of indigenous populations into emblems of national identity. Under the regime of authoritarian president Porfirio Díaz, technocratic elites had viewed rural artisans as a hindrance to progress. But in the 1920s, the new leadership embraced living traditions, organizing projects such as the 1921 Exposición de arte popular in an effort to forge a unified culture from a war-torn nation. Even as the country industrialized, designers returned to vernacular forms and materials. Clara Porset adapted the butaca, or chair, to a distinctly Mexican version of modernism, while Ramón Valdiosera updated the china poblana costume to create styles more suitable for urban women.

Artists and designers in both Mexico and California romanticized the former’s indigenous artisans, adopting elements of traditional crafts and reimagining native rituals. In Mexico, the post-Revolution government elevated the handcrafts (called “popular art”) and customs of indigenous populations into emblems of national identity. Under the regime of authoritarian president Porfirio Díaz, technocratic elites had viewed rural artisans as a hindrance to progress. But in the 1920s, the new leadership embraced living traditions, organizing projects such as the 1921 Exposición de arte popular in an effort to forge a unified culture from a war-torn nation. Even as the country industrialized, designers returned to vernacular forms and materials. Clara Porset adapted the butaca, or chair, to a distinctly Mexican version of modernism, while Ramón Valdiosera updated the china poblana costume to create styles more suitable for urban women.

In California, the idealization of traditional craft represented a larger pursuit of “authentic” experience. Industrialized societies revered native cultures as “purer” and attuned to nature, imbuing handmade goods with a halo of time-honored practice. Mexico’s official exhibitions and publications made its traditional crafts accessible to Californians, who reconfigured folk forms and techniques in their art as well as commercial products. Enamored by folk art as well as the people who made it, designers and craftspeople journeyed to small villages, seeking a rural idyll as a respite to fast-paced city life.

While much as been written about the embrace of international modernism in Mexico, few have addressed the impact of progressive California design and architecture there. Mexican architects were deeply influenced by their California counterparts, especially the Case Study Houses published between 1945 and 1966 in editor John Entenza’s Arts & Architecture magazine. And not only did architect Richard Neutra have a profound impact in Mexico, he also helped bring recognition of Mexican modernism back to California. He was one of several native or adoptive Californians who proselytized for the country’s new architecture and design. Furthermore, architecture writers such as Esther Born, Irving E. Myers, and Esther McCoy introduced Americans—particularly California readers—to under-recognized buildings worthy of comparison with the best in modern architecture.

The narrative of California/Mexico exchange continues to the mid-1980s as major California architects such as John Lautner began working in Mexico in the 1970s; and conversely, Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta began receiving commissions in California in 1985. Chicano muralism thrived in communities such as San Diego’s Barrio Logan and in East Los Angeles, where it continues to function as a unifying marker of identity.

Additionally, the exhibition’s 1915–1985 survey allows a comparison between the Mexico City Olympics in 1968 and the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984. The bold graphic and environmental design program devised for Mexico 68 had a marked influence on the visual language of L.A. 84. In both places, graphic design was essential to way-finding schemes as well as to each city’s distinctive branding. The exhibition concludes with comparisons of burgeoning growth and urban sprawl as well as new voices of dissent in both places, all attesting to the richness and complexities in an ever-evolving dialogue.

Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985 will run September 17 through April 1, 2018 at LACMA’s Resnick Pavilion. For tickets and information, visit lacma.org

Did Drought Play a Role in the Golden Age of Skateboarding?

A new photo book captures the rawness of a cultural movement.

Can Technology Produce a Better Bottle of Wine?

Hahn Family Wines in Salinas brings IoT to the farm with a Verizon AgTech partnership.