A New Generation Brings Fresh Relevance to an Iconic Brand 60 Years Young

Think Bing.

-

Posted onDecember 24, 2019

-

CategoryArtisans, Arts + Culture, Makers + Entrepreneurs, Small Businesses, Time Capsule

-

Written byTodd Prodanovich

-

Photographed byGrant Ellis & Bryce Lowe-White

It’s a cool, fall morning in the cruisy coastal suburb of Encinitas, and Matt Calvani is just shifting things into gear at the Bing Surfboards factory. Matt is in his late 40s with short-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair, but his expressive, blue eyes carry a youthful spark—even when he’s jetlagged.

Just a few days ago, Matt was in France for a stint building gorgeous surfboards of all shapes, sizes and colors for the local surf community. On that side of the Atlantic, they really appreciate the quality and craftsmanship that the Bing label represents. They appreciate it on this side too, as a matter of fact.

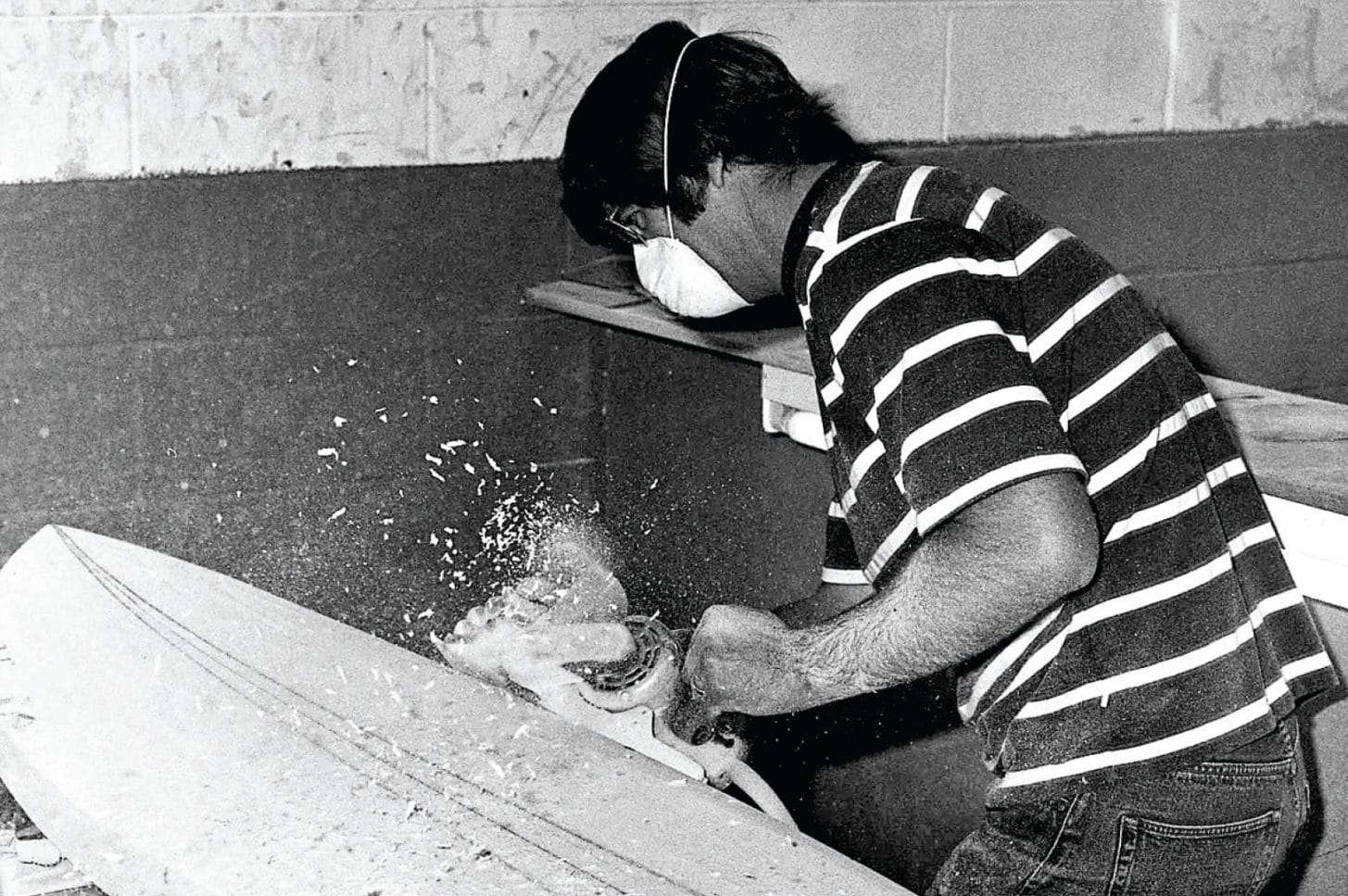

Matt walks me through the sprawling factory past boards in every stage of production. Racks are jammed with crude polyurethane blanks begging to be transformed into refined wave-riding tools. There are finished, twin-finned fish shapes that will soon be airbrushed in cosmic colors in the next bay over. A traditional, single-fin longboard awaits its gloss coat. To surfers, surfboards are precious objects—and they’re treated as such through every step of the production process at Bing.

“Once the glosser starts on this one, he’ll close all the doors and make sure there’s no airflow whatsoever,” says Matt. “When you’re glossing boards, even the slightest movement of air will cause ripples in the deck, and you can’t have that.”

Matt’s been meticulously building high-quality boards at this factory for the past nine years, and before that he was shaping under the Bing label for another decade in Hermosa Beach. In that time, Matt has turned Bing into a surfboard brand synonymous with the ride-anything ethos of modern surfing—a global, cultural shift away from the thin, narrow, difficult-to-ride boards used by competitive surfers on the World Surf League’s Championship Tour. The shift is toward a whole galaxy of wider, thicker, endlessly fun shapes that cater to average Joes and surf savants alike.

Today the best surfboard shapers often find inspiration in surfing’s past, taking the fuller outlines of ’60s and ’70s craft and giving them a modern tune-up—more refined rails, new fin templates and configurations, hydrodynamically superior bottom contours, etc.

“Taking the old design elements that offer really nice feelings in the water and then tweaking them to make them easier to ride—that’s where a lot of the magic is,” says Matt. “A lot of those classic boards were actually really hard to surf, but there’s still something special that you can tap into.”

Matt doesn’t have to look far for that kind of inspiration. He can find it in the dusty boards hanging in the rafters of the factory, in the old Bing posters and artwork hanging in the shaping bays, or on the phone with guy who started it all: Bing Copeland, whom Matt considers a father figure and speaks with regularly.

Bing Copeland with his grandfather.

Herbert Bingham Copeland III, as his birth certificate reads, is a pretty inspiring character whether surfboard design is your thing or not. From when his babysitter first decided to call him “Bing” instead of “Herbert” to when his surfboard brand became one of the most renowned on earth, Bing’s is one of the most dynamic surf industry origin stories you’re likely to find.

Born in Torrance in 1936 and growing up in nearby Manhattan Beach, Bing had a front-row seat for the birth of the modern surfing industry. In Think Bing, the expansive new documentary by South Bay-based filmmaker Bryce Lowe-White chronicling the brand’s 60-year history, Bing talks about sitting on the sand by the pier as a 12-year-old, watching surfers like Dale Velzy riding their then-crude planks, when another young boy came and sat in the sand next to him. It was Greg Noll, who would grow up to become one of the most famous big-wave surfers in history.

Neither of them could have guessed that as they sat in the sand, mind-surfing the Hermosa peaks, they were starting a friendship that would last a lifetime. The two were surf friends through and through, hauling sleeping bags down to the sand to be ready to surf at first light when the conditions were prime, and occasionally bumming rides south to San Onofre or north to the perfect points of Malibu and Rincon.

Eventually Bing’s thirst to ride bigger and better waves took him to Hawaii, where he lived with fellow Hermosa surfer Rick Stoner and joined the Coast Guard to stay in and around the powerful Hawaiian surf. But it was a wildly ambitious surf voyage away from the Hawaiian Islands that introduced Bing to the vocation that would define his surfing life.

Bing and Rick wanted to taste high adventure and score new waves, so in 1958 the pair set literal sail—touring the Pacific and countless exotic surf breaks in the process. Tahiti, Fiji and Samoa were all on the itinerary, as was New Zealand, where they introduced modern surfing to the country after coming ashore in Auckland.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

In Think Bing, Bing recalls there being 10 or 15 locals in the water, many of whom were accustomed to riding waves on a surfski—a kayak-like, surf-catching craft. When they saw Bing and Rick calmly gliding and trimming on their surfboards, the locals were lining up for a chance to borrow the boards and slide a few peaks themselves. Wanting to spread the stoke and leave the Kiwis with some craft of their own, Bing sourced some Styrofoam and hacked it into a half-dozen boards with a cheese grater.

“They were kinda crude,” Bing admits, “but they were OK, and I remember thinking to myself, ‘You know, I can do this.’”

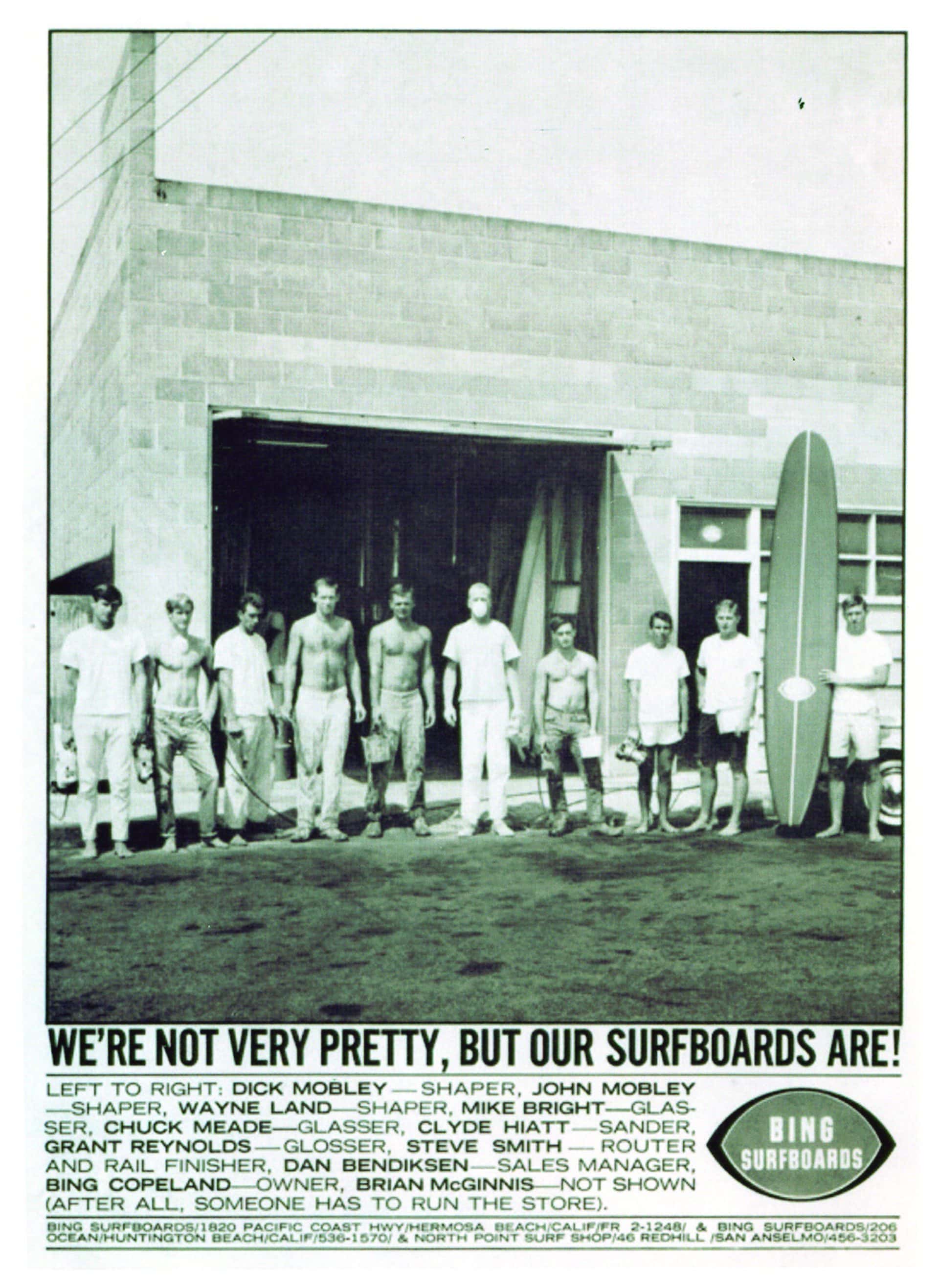

“This” was, of course, building surfboards. When he returned to Hermosa Beach to begin in earnest, he armed himself with much more than a cheese grater. Bing and Rick opened a shop together in 1959 and started churning out Bing & Rick Surfboards, which later became Bing Surfboards when Rick left to pursue lifeguarding.

That era of board-building in Hermosa Beach was one of the most explosive and influential in the history of surfing. Hollywood ignited a powder keg of surf popularity with the 1959 film Gidget, which would be followed by countless beach-romp imitations throughout the decade—escalating the popular fascination with surfing into a kind of hysteria. Founded by filmmaker John Severson in 1960, Surfer Magazine created both a center of gravity that the nascent culture could revolve around and a place for upstart board brands to advertise their wares.

Bing, Greg, Hap Jacobs, Dewey Webber and more set up shops on the Coast Highway, and to say that business was good would be an understatement. “We could sell as many [boards] as we could make in those days,” says Bing. “More than a surfboard, we were building a social scene, which we didn’t really realize we were doing at the time. But that’s what we did.”

“More than a surfboard, we were building a social scene, which we

didn’t really realize we were doing at the time. But that’s what we did.”

Bing built a stable of team riders that included many of the most influential and stylish surfers of the era, including David Nuuhiwa and Donald Takayama. Bing enlisted legendary Hawaii-based shaper Dick Brewer to help on the board design front, and Dick created the Bing Pipeliner model, which set surfing’s collective imagination ablaze when ridden in barreling Hawaiian surf.

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, everything changed in the surf world, just as things did worldwide with the growing counterculture movement. Hair grew long, surfboards got short and Bing had to evolve or risk getting left in the dust. Electric young surfers Keith Paull and Rolf Aurness joined Bing, the latter of which went on to win the 1970 World Championships in Victoria, Australia, on a 6’10” Bing board.

Bing found a great friend and collaborator in Duke Boyd, who helped define the look and feel of the brand amid the cultural upheaval. And in 1973, Bing began a pivotal collaboration with a pair of mad surfboard scientists, brothers Malcolm Campbell and Duncan Campbell, who were some of the first to experiment with three-finned boards in their garage in Oxnard, California—creating the Bonzer design and opening up entirely new possibilities for riding waves.

Amid all the excitement ushered in by the new era of surf culture and board design, however, Bing was beginning to feel estranged by the new landscape—“because of those drug influences, basically, and the hippie influences … not that I disagreed with all that stuff, but it seemed to lead surfing and our customer base in a bad direction,” he says. “I could see my interest slipping away.”

Business had also slowed, in large part due to the atomization of the surfboard industry, with independent backyard shapers popping up left and right, disrupting the big manufacturers of the time. In 1974 Bing sold the Bing license to Larry Gordon, the San Diego surfboard mogul of Gordon & Smith fame. Bing was ready for a change of pace, and he chose a drastic one at that—trading the crowded beach scene for some wide open, snow-dusted spaces in Sun Valley, Idaho.

The Bing label lived on in some form under Gordon’s ownership, then under former Bing head shaper Mike Eaton, who also produced boards under his own label, Eaton Surfboards. Mainly, however, the Bing label languished from the late ’70s until 2001, just waiting for someone to see the value in its legacy and its potential to return to greatness. Enter Matt Calvani.

“Right away I knew he had something going. I liked him,” says Bing of his first meeting with Matt, who had expressed an interest in picking up the brand’s torch and running with it, reviving some of the classic designs and creating some new ones of his own. “He was the perfect guy for the job. I was impressed with his quality, his shaping, his understanding of both shortboards and longboards.”

“My first impression of Bing was that he was just super-nice and approachable, and I really liked him off the bat,” Matt tells me in the Encinitas factory. “Most of the time, when you have a partnership, things get difficult at times. But with Bing, he’s just such a good guy and so easy to work with. He’s a legend, but he doesn’t have a big ego. He’s just stoked to have someone interested in his brand and taking it in a good direction. To this day, it’s like that.”

Since then, Matt has worked closely with stylish California surfer and Bing team rider Chris Del Moro to produce fuller-volume shortboards like their best-selling Dharma, as well as more far-out design ideas like the Speed Square, which is essentially a foam-and-fiberglass boogie board that’s meant to be ridden standing up. Matt and Chris’ collaborations have worked like magic under the feet of countless surfers, including Australia’s Dave Rastovich, who’s widely seen as the most talented free-surfer of a generation.

Before Bing, Matt spent years cutting his teeth shaping boards for labels across the South Bay. He was thrilled to not only resurrect the classic models that had first earned the brand acclaim but also to follow his creative impulses wherever they led.

“We were ahead of the curve with the Simmons-inspired boards, fish, quads and wings,” says Matt about the interest in alternative shapes that first caught fire in the 2000s and has turned into a roaring blaze since. “Like Bing was trying to do in the early ’70s, since the 2000s we’ve really wanted to do things our own way. You can go with the trends of what people want to ride, but you need to make it your own at the same time.”

Matt has no shortage of ideas for new Bing models and tells me about the potential he sees in the mid-length movement—boards between roughly 7 feet and 8 feet in length, which don’t quite fit into the longboard or shortboard categories—when combined with twin-fin setups and channel bottoms. It’s a design concept he’s seen work to a spectacular degree under the feet of Australian surfer Torren Martyn. Now it’s just a matter of figuring out how to make it in a uniquely Bing way.

Matt takes me up to a storage loft—a place he goes from time to time for a little inspiration. He pulls a slightly yellowed, early-’60s longboard with a giant wooden fin—three stringers running down the middle and two strips of inlaid wood crossing each other, and the stringer looking oddly like the double helix of a DNA molecule. “I know you’d take a template and a router to do the inlay, but the crossing in the center …”

He scratches his chin while feeling the deck of the board. “I don’t know how Bing did that, but he did it perfectly.” It’s a beautiful surfboard, but it’s more than just that. It’s something different, something built to last, something Bing.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

U.N.K.L.E. and Thieves Like Us Headline This Year’s Guadalupe Valley Wine, Food and Music Festival in Baja

Celebrate the harvest season with

a Mexican touch.

Three California Destinations We’re All Over This Fall

Take advantage of mild climates, smaller crowds and local charms at these autumn-friendly weekend getaways.

KCET’s Artbound Returns With a Look at Notable California Artists

First up, Light & Space.

Get the Latest Stories